[Image: “Glenn Ligon @ the Bronx Museum of Arts” by Steffi Njoh Monny, via CC BY-ND 2.0.]

[Image: “Glenn Ligon @ the Bronx Museum of Arts” by Steffi Njoh Monny, via CC BY-ND 2.0.]

I’m listening to Cecil Taylor’s Silent Tongues as I write this (which you can listen to too as you read this), a live album I found my way to by way of Fred Moten and Kandice Chuh, whose fall 2014 course—the latter’s—“Black, Brown, and Yellow: On Ways of Being and Knowing” began with the former’s “The Case of Blackness” (2008). This opening sentence feels a bit confusing to read, as I review it, but I’ll let it be in keeping with the openness of this project to difficulty, to trying to express something beyond the available, or hegemonic, frames. In this way, the project—what I’m calling “Black Social Music,” after Moten and Miles Davis—is true to both Moten’s and Chuh’s aims, as it is, also, to Alexandra T. Vazquez’s, whose method of “listening in detail” as a way to cognize the uncognizable orients this project too.

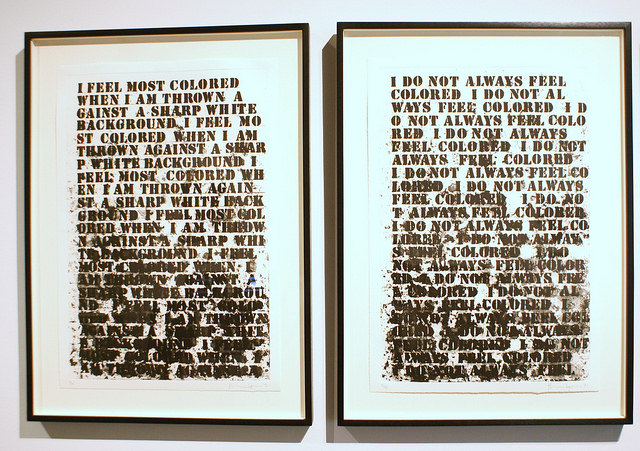

Frames are a way of casting a way, a path between edges, and the albums I think about on this site, all by black subjects, do that: they escape the categories to which white supremacy, in its manifold operations, would restrict them. The two Glenn Ligon works above, based on Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay “How It Feels to be Colored Me,” visually demonstrate this dialectic between containment and excess: on the one hand, they show the “white background” upon which racialized subjects find themselves defined, a definition that’s underscored by the Hurston quotations about being “colored,” but on the other hand, the black letters, and the subjectivity they express, shade into illegibility—they exceed the frame of readability, of knowledge. As such, they point the way to a different knowledge, one beyond the grasp of dominant onto-epistemologies of blackness. Indeed, though the Ligon prints above are small and framed, their original versions take the form of 80-inch-tall doors (as Ligon explains in this audio clip), making them both monumental and thresholds one can stop at or move through.

This doubleness of blackness, as both interdiction and escape, is the problematic Moten explores in “The Case of Blackness,” counterposing the racialization of the visual with the fugitivity of the sonic. The essay’s key passage in this regard, and from which this project takes its name, is as follows:

In other words, the notion that there is no black social life is part of a set of variations on a theme that include assertions of the irreducible pathology of black social life and the implications that (non-pathological) social life is what emerges by way of the exclusion of the black or, more precisely, of blackness. But what are we to make of the pathological here? What are the implications of a social life that, on the one hand, *is not what it is* and, on the other hand, is irreducible to what it is is used for? This discordant echo of one of Theodor W. Adorno’s most infamous assertions about jazz implies that black social life reconstitutes the music that is its phonographic. That music, which Miles Davis calls “social music,” to which Adorno and Fanon gave only severe and partial hearing, is of interdicted black social life operating on frequencies that are disavowed—though they are amplified—in the interplay of sociopathological and phenomenological description. How can we fathom a social life that tends toward death, that enacts a kind of being-toward-death, and which, because of such tendency and enactment, maintains a terribly beautiful vitality? (188)

In other words, “this matrix of im/possibility” is “the position,” as Moten writes a moment later, “which is also to say the problem, of blackness”—an echo of Du Bois’s formative question, “How does it feel to be a problem?,” which both Hurston and Ligon echo as well. The sonic—Davis’s “social music”—is constituted by this paradox of im/possibility too, but in Moten’s account it seems more generative of possibility than the visual or the textual, given the “frequencies” that air and “amplify” “interdicted black social life” (even if they’re “disavowed”).

As such, this project takes examples of “black social music”—that is, music produced by black subjects—as the ground upon which to examine this im/possibility of blackness: to think about how these musicians were both framed by, and exceeded the framing of, whiteness. Though some of these artists were responding to record-industry pressure, or wider social and political pressures, or to the embedded anti-blackness of the U.S. at large, they were also, at the same time, responding to their own aesthetic pressures to express what they desired. And yet, as irreducible as this latter context is, the bulk of critical/scholarly attention to these musicians is weighted to the former: to how they contended with externally imposed frames, whether the civil rights movement in the case of the earliest album included in this project (Max Roach’s We Insist!), white record buyers in the case of the two Miles Davis albums here (In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew), or social unrest, as in the example of Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On. Adorno, as Moten notes, is an example of this inability to hear beyond the frame of whiteness: in his 1936 essay “On Jazz,” he famously dismissed the form as insufficiently aesthetic—a mere commodity.

Vazquez also cites Adorno, in the outro to her book’s intro, quoting him as such: “Music reaches the absolute immediately, but in the same instant it darkens, as when a strong light blinds the eye, which can no longer see things that are quite visible” (42). The line comes from his essay “Music, Language, and Composition” (1953/1956), in which he analyzes the relations of music to language and subjectivity, but he draws upon the canon of classical music, and the new music of Webern and Boulez, as well as a universal subject, to make his case. So while Adorno’s notion of music disabling sight is a generative, if ableist, one, the metaphor is colored by his overall Enlightenment frame: light gone dark by absence.

To counter this critical tradition, then, I try to hear these black-identified artists’ fugitive frequencies—the “off harmonies,” to extend a Moten phrase, of black social life in the face of its putative absence. Put another way, and as the design of this site’s landing page graphically represents, I take blackness as the “sharp” “background” against which my own white U.S. subjectivity is troubled, my musings about these albums mere imprints in a vast, complex surround I can only partially hear. Indeed, some of these albums resist cognition altogether, such as Taylor’s Silent Tongues, the latest album in this project (though 40 years old at this point). I pause with this set in part because it instantiates a cognitive limit and in part to signal forward to future albums I’d like to think about here, as I continue my studies and develop my dissertation, which takes the possibilities of the sonic as a constitutive question.

But this project is already unfinished: I’ve yet to post my thoughts—hearings, or listenings, is more apt—about most of these albums. In this regard, I hope you, as a visitor to this site, will contribute what you hear via the comment box at the bottom of each album page.

A few further notes about this project:

On the method of my commentaries, and your readings of them, and our mutual, if asynchronous, listening—

Each commentary is meant to be read as the album’s music plays, and I’ve included the music via YouTube recordings at the top of each post, with the instruction, in maroon type, to begin playing the music before reading. In a few cases (such as with Albert Ayler’s New Grass), I’ve written the commentary in time to the music, so that I make certain points about the music in direct reference to the parts of the music where those points are applicable.

I foreground the music not simply so that you hear it, befitting a project on music, but so that you read my thoughts, and generate your own, at the same time as you hear the music. If my goal in this project is anything, it’s to induce a greater connection between the sonic and the verbal, between hearing and reading, especially as an academic method. Fortunately I had the opportunity to create this digital project as part of my Ph.D. coursework in English, but all too often the sonic is divorced from the specifically textual in humanities studies outside the discipline of (ethno)musicology. I hope the increasing attention to sound, as signalled by Moten, Chuh, and Vazquez, among many others, augurs a fuller embrace of “intermedia” studies in various aspects of higher education. We live our lives, for those of us with the privilege of hearing, in sound, so why should it be separated from our academic work? Indeed, consciously bringing sound into our academic lives may contribute to a greater commoning of higher education, in line with other methods of transformational praxis vis-à-vis the university.

On the assemblage of elements on this site—

I’ve posted YouTube recordings of the albums both so that the album covers or other visual material are part of the experience of listening and because YouTube is relatively open access, though in one instance there’s an automated ad at the beginning of the recording (which I’ve noted accordingly).

The design theme of this WordPress site, Minimatica, was a fortuitous find, given the landing page’s graphical reflection of the counter-hegemonic aims of the project. But there are limits to the design: this typeface is not the easiest to read, for instance, and I wish the frames on the landing page simply included the artist and album title and not also the beginning lines of the commentary. I hope to address such issues in the future.

On the time frame of creating this site—

As the date stamp at the top of this page indicates, this post, and the bulk of this project, was created, first, while grand juries in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, were considering whether to bring charges against the police officers who murdered Michael Brown and Eric Garner, respectively, and, second, during the uprisings that followed those officers’ non-indictments (on November 24th and December 3rd). I participated in some of these actions here in New York City, and I watched many more on video (such as this documentation of a blockade of the Oakland police headquarters, stunningly orchestrated, in terms of music, sound, performance, and organization, by three black-identified activist groups).

Though the sounds of uprising are myriad, the one that has stuck out to me is of NYPD helicopters hovering and circling above the East Village, where I live, not far from Union Square, an epicenter of the actions: the drone of blades and motor a sonic connection between U.S. domestic and foreign policy concerning racialized subjects and political economy. I had lamented this sound as an audible form of repression, drowning out the terribly beautiful vitality of the uprising, of the ongoing, centuries-long movement to defend black social life from premature death, but I realize now I had it wrong—that I wasn’t thinking sound otherwise. The NYPD drone is actually a joyful noise, because it means, once again, that the state is on the defensive from this latest sustained challenge to its imperious rule.

—SMK, December 20th, 2014